Ryan, Lee, and Carolyn were all there, but I have no recollection of their response to the “slightly venomous” creatures that occupied our space; my only recollection is getting out of there! Of course, I did possess the presence of mind to walk clockwise, around the hearth, to exit the Hogan.

Hogan Lesson

I have always heard this word pronounced Ho~gun. On this trip, however our Navajo guide Eric, suggested that we stay in his family’s traditional Hogan instead of erecting our tents for the first night of our trip. He pronounced it HO~gahn. The Hogan is a sacred home for the Navajo people who practice traditional religion within the tribe. Some are used as homes, and others as ceremonial places to keep the individuals in balance. The female Hogan’s are often made of wooden poles, tree bark and mud. Doorways of the structures face east to meet the morning sun, and upon entering the dwelling, everyone should move clockwise, to follow its daily path. There are two types of Hogan’s: Male and Female. Male Hogan’s are temporary structures that can be moved or taken down. Female Hogan’s are permanent structures. (See citation information at end of story for all sources throughout.)

Although we were honored to be offered such accommodations, I was skeptical; because I feared that a snake could crawl across the dirt floor of the Hogan and get in my sleeping bag, I almost said “no thank you” to the offer. Weakening to peer pressure, I spread my bed roll like the others and settled in. Additionally, we were offered traditional sheep skin pallets to lay on the ground beneath our bedding, however we all opted for our own tradition of inflatable pads that we would pack with us on the 38 mile journey around Navajo Mountain. Scorpions aside, the Hogan offered just the kind of nostalgia that we were in search of on this trip.

Navajo Mountain

Rising to a height of 10,388, Navajo Mountain is a laccolith, first called “laccolites” by Grove Karl Gilbert, the Geologist who pioneered the information of “Bubble Mountains” in his field notebooks. He studied the nearby Henry Mountains, also laccoliths, and determined that “the Henry’s were formed by molten igneous rock welling up through sedimentary strata, then bulging out along bedding planes into mushroom-shaped sills. The intrusive bulging pushes up the overlying sedimentary strata into dome-shaped mountains”(Fowler). According to Don Fowler’s Glen Canyon Country, Gilbert’s study is one of the world classics in geology.

Located in San Juan County, UT (and a portion of Coconino County, AZ), on the Navajo Nation tribal lands. Navajo Mountain has sacred meaning to three Native American tribes in the region: The Navajo, Hopi, and the Paiute. It is necessary to garner the correct permit to hike anywhere near it. Luckily, the Navajo Nation welcomes backpackers to see their beautiful land and for $12 per night, per person, it is one of several special hikes that you may purchase a permit for. However, don’t get any ideas about summiting Navajo Mountain; it is sacred and the tribe does not allow visitors to attempt the summit. It is always best to check their website for updates, availability, and general rules about hiking on tribal lands.

With our permit securely zipped into Ryan’s pack, the four of us, loaded into the Suburban with Eric. He drove us to the southwest side of the mountain and the site of the old Rainbow Lodge where he shared history with us about the area. The lodge was built in 1923 and hosted many a tenderfoot until 1951 when it burned to the ground.

John & Louisa Wetherill and Rainbow Bridge

The Wetherill family settled in Colorado’s Mancos valley in 1880, established their Alamo Ranch, ran cattle in Mancos Canyon and on Mesa Verde (Fowler). They are important to us because the sons of the Wetherill family officially “discovered” places in our current day Mesa Verde National Park, such as Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House. The family’s discovery of these historic locales led to the preservation and recognition of past cultures and their artifacts. Mesa Verde’s unearthing is credited mostly to Richard and Al Wetherill, but eventually, brother John would get in the mix as their explorations moved westward into the Glen Canyon Country of southeast Utah. Once married, John and Louisa opened a trading post in 1900 just north of Pueblo Bonito (Chaco Canyon), called Ojo Alamo Trading. Later, they moved to Oljato in Utah.

John and Louisa were career guides who traded goods and artifacts for many years. There are reams of stories with their names weaved like tapestry into the framework of the southwest. For our story however, we’ll note that Louisa was the first to help guide the public to Rainbow Bridge, via Navajo Mountain.

In 1908, John was scheduled to lead Byron Cummings, a University of Utah professor, to several archaeological sites. During a stopover at Oljato, Louisa mentioned to Mr. Cummings that while talking with local Navajos about the bridges of White Canyon (Cummings helped to get Bridges National Monument mapped and designated.), they told her of a “bridge somewhere toward Navajo Mountain ‘shaped like a rainbow.’” At that time, he promised to come back in 1909, to find the rainbow! (Fowler)

True to his word, Cummings came back in ’09 and John guided not only him, but William Douglas as well to a joint “discovery” of Rainbow Bridge.

For many years, John Wetherill guided tourists to the natural stone bridge spanning Bridge Creek, including Teddy Roosevelt, Clyde Kluckhohn, and Zane Grey. The trail was long, hot, and arduous, however it was worth toiling through the rocks, deep sand, and cactus to observe the splendor of the canyons.

President Roosevelt did not get the honor of creating Rainbow Bridge National Monument; that task was left for President Taft in 1910. He did however, get to journey to the Rainbow in 1913 to see it firsthand.

In 1923, soon to be esteemed anthropologist, Clyde Kluckhohn, made his first trip to Rainbow Bridge. Because he could not afford the services of John Wetherill, he and his partner set out on their own to find it. Fascinated by the country and the Navajo people who lived there, Kluckhohn was inspired to learn the language and study them. One nuance of this was the discovery of their native language names for Rainbow Bridge. The Navajo refer to it as “Tsay-nun-na-ah—Rock Goes Across the Water” or in the Kayenta Region, “Nonnezoche.” The Paiute call it “Barohini—the Rainbow.”

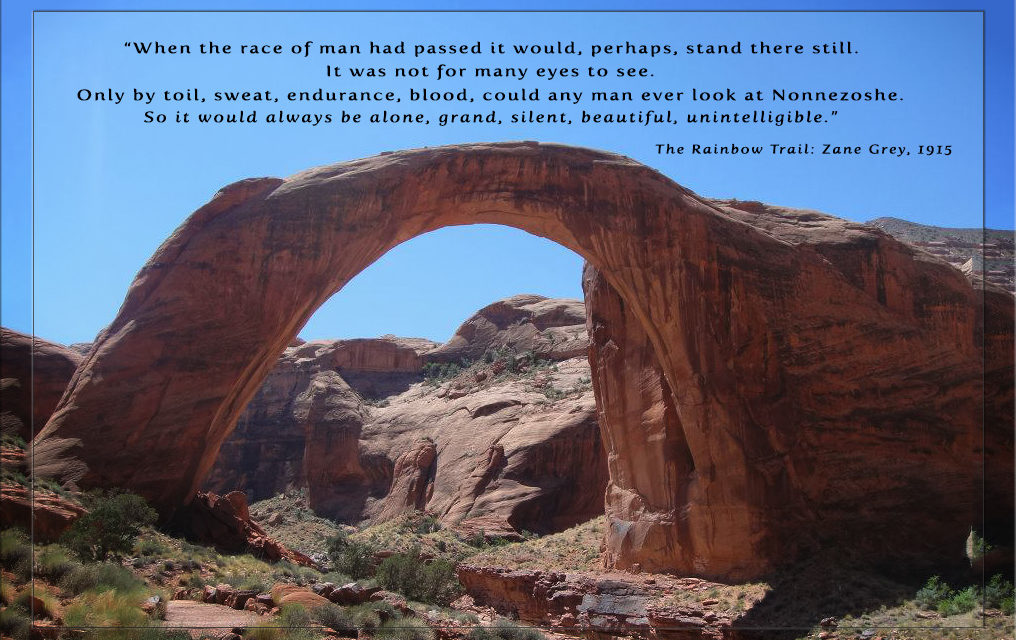

Zane Grey arranged several of his novels in the Glen Canyon Country including The Rainbow Trail (sequel to, Riders of the Purple Sage), Wild Horse Mesa and others. When Grey’s character, John Shefford, said:

“When the race of man had passed it would, perhaps, stand there still.

It was not for many eyes to see.

Only by toil, sweat, endurance, blood, could any man ever look at Nonnezoshe.

So it would always be alone, grand, silent, beautiful, unintelligible”

It is a sure bet that neither of them knew what would befall Glen Canyon and the Colorado River in the near future. Glen Canyon Dam would ensure that many tourists would have the gratuitous privilege to look upon Rainbow Bridge.

We said goodbye to Eric, whom we would not see for 4 nights and 5 days, then headed down the rocky trail that had not seen improvement for quite some time. Navajo Mountain loomed to our right and ahead of us, far away across the unseen Colorado River rose the Kaiparowits Plateau; all large landmarks that we would need to stay within the confines of for a successful trip. To the north, should we reach the San Juan River, we’d obviously gone too far.

Consulting the maps, we were at 6,280 feet leaving the site of Rainbow Lodge. We would climb to 6,600’ and descend to 6,480’ in Cliff Canyon. By the time we reached Redbud Pass, we had descended to approximately 4,500 feet. Upon reaching Rainbow Bridge, our elevation will be just under 3900 feet. I am pretty sure that the translation here is quite a bit of climbing to reach our end goal on day five.

An accidental photo by Carolyn early in the trip shows the condition of the trail. Our packs were heavy and included food, water, clothing, first aid, toiletries, camp shoes, tents, sleeping bags, sleeping pads, and anything that we deemed necessary to survive in the wilds of Utah. Our food supply would lessen as the trip went on, thus reducing weight in our packs, but it was necessary to replenish water every time we found a source.

An accidental photo by Carolyn early in the trip shows the condition of the trail. Our packs were heavy and included food, water, clothing, first aid, toiletries, camp shoes, tents, sleeping bags, sleeping pads, and anything that we deemed necessary to survive in the wilds of Utah. Our food supply would lessen as the trip went on, thus reducing weight in our packs, but it was necessary to replenish water every time we found a source.

We chose the month of May because it is generally optimal desert hiking weather. Theoretically, it should not be too hot, too cold, or too dry.

Our days were hot, soaring well into the 90’s, but the nights were comfortable. Some of the creeks were still flowing down the sides of Navajo Mountain, but we all agreed that if temperatures remained the same or rose, within 2 to 3 weeks, water would become scarce. At every water crossing we would “slam” the water from our Nalgene bottles, drinking a liter each, and then filter more water into our bottles and packs; we were careful to never run out and always stay hydrated.

The desert was alive with greenery and flowers bloomed all around us. Carolyn stopped to photograph the lovely Cliff Rose, but the intoxicating smell was definitley the cause of her headache. Other flowers she photographed along the way were the Sego Lily (my favorite!), Mormon Tea, yellow and pink Prickly Pear, Globe Mallow, and countless others.

In the evening, Lee finds a campsite among the cliffs with a soft sandy bottom and remnants of hanging gardens. His “perfect” campsite is at the bottom of a large pour-off, in a would-be pool. Should it rain, we were screwed.

Rules of the desert: If it rains 20, 30, or 100 miles away—all that water may possibly come at you in a rush, and you will likely drown if you are anywhere near a creek, gulley, drainage, or camping under a large pour-off.

So we pitched our tents in the bottom of the dry pool. It was beautiful and the sand on our bare feet was luxurious!

Watching over us throughout the night would be Carolyn’s talisman who lives in her backpack; ebay Buddha. He came from China years ago, via a $6 purchase. Since that time, he has climbed 14ers, forded creeks, snowshoed valleys and mountains, he has even been to the top of Mt. Kilimanjaro in Africa; now, he accompanied us on this sacred voyage around Navajo Mountain, in search of the Rainbow.

As we traversed along on day two, we came across several male Hogan’s and infrequent panels of rock art. More flowers were also found along the way including a desert favorite: Sacred Datura. “Should you eat this, you will hallucinate, and most likely, you will also die” stated Carolyn’s caption for the photo she posted on Facebook after our trip.

Sacred Datura

This elegant, white, trumpeted flower of the desert is a narcotic. If not properly prepared for consumption, it is lethal—Do Not try this at home. Also known as Jimsonweed (old cowboy songs talk about the Jimsonweed!), it can be found throughout the southwest, and is known for its qualities to help a person let go of reality without feeling threatened.

One modern day peddler of Sacred Datura—oil ?—suggests that, should you suffer from patterns of imbalance such as “disintegration of a known familiar reality, shattered dreams or ideas, feelings of your ‘being’ being dissolved, or if you feel like an alien,” you could benefit from the “harmonizing qualities” of this particular snake oil, I mean, Sacred Datura, that they are selling in a 10ml bottle for $10.50.

The Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum warns: All parts of these plants contain numerous toxic alkaloids. One of them is scopolamine, a common ingredient in cold and nausea remedies. Shamans in various cultures have ingested datura to induce visions. This is one of the most dangerous plants used for this purpose, because not only do individual plants vary in potency, but humans also differ in their tolerance to the toxins. Despite widely-published warnings, every year a few people suffer life-threatening poisoning from eating this plant; some of them don’t survive. Again, Do Not try this. Appreciate the beauty of this flower as you walk past one in the desert, but do not attempt to use it in any way.

When Eric dropped us off the day before, he mentioned a place where we could find remnants of caved in Kiva’s in a side canyon. Ryan and Lee thought that sounded cool. We stashed our packs at the head of said canyon and went in search of the underground, ancient ceremonial chambers.

With water bottles in hand, our hike led us beside a dry creek bed and towering walls of sandstone—oh wait—that’s really not much different than the trail that we left, except this one really had no trail. As we trekked on, the walls narrowed and small rock basins began to appear. The creek bed turned from sand to Navajo Sandstone and the centers of the pools held water that was clear and free of algae.

Coming around a bend in the creek, the trail opened and a trickle of water disappeared over a small precipice. With plenty of room to walk around the edge, we could see the waterfall was approximately 30 feet high. Below was a deep pool of clear, enticing water! With the search for Kiva’s forgotten, it was time for a swim. As I approached, there was Lee, cavorting like a river otter through the water in his underwear. He said we should all be thankful that he left them on.

After the unexpected luxury of an afternoon swim, we returned to the trail. We traversed Redbud Pass slowly and marveled at the tenacity it must have taken years ago to blast away with dynamite, the narrow passage connecting Cliff and Bridge Canyons. The terrain was steep and rock strewn with foliage growing over the trail in places. The 1000 foot walls, standing close on either side of us, provided shade that was splendid for the challenging climb to the top—unless you’re Lee—then you just run to the top and mock those below, as they toil away.

While descending the other side of Red Bud, we found it necessary to crawl and slide down large boulders. Rockfalls and floods have destroyed the trail rendering it unfit for horse and mule traffic; the popular form of travel many years ago when the Wetherill’s and other guided parties visited Rainbow Bridge.

We soon found accommodations for night two on a rocky outcropping. As we finished setting up camp and boiled water for our 5 Star bag meals (dehydrated food—it’s the best!), we noticed some birds swooping wildly through the sky. We had the rare opportunity of watching as two Peregrine Falcons tag-teamed a Swallow they intended to eat for dinner. One Falcon would dive at the Swallow and it would evade, only to run head-long into the other one. I found myself rooting for the Swallow, but I knew with certainty that the Falcon’s would win. Not wanting to see the ways of nature unfold before me, I averted my eyes.

Every day we woke to sunshine and warmth, and day three was no exception. I noticed that Buddha sat to meditate in a couple of different places that morning; one in front of a great Prickly Pear Cactus, and once facing the trail that lead to Rainbow Bridge. With blessings bestowed, we hefted our packs and marched. Upon reaching a fork in the trail we decided to stash them, and travel “sans packs” to the Rainbow and back carrying only our water bottles and trash.

Home of the Rainbow

There are many stories of why Rainbow Bridge is sacred to Native American tribes, but none have caught my attention and felt so full of beauty and meaning as this one:

“two Rainbows, a male and a female one, arching together in perfect marital union.

Now this certainly explains how all sorts of Rain people, such as young Rainbows

and Clouds, originate from this place and float from here into Navajo-land to bless its

plants, its animals, and its people with moisture and with life….This place is the very

Home of the Rainbow.” (Luckert 1977: 17-24. Fowler, 2011)

This excerpt is from a time when the Navajo people felt it necessary to guard and protect Rainbow Bridge from the encroaching waters of Lake Powell. In 1971, the water, that was never supposed to reach Rainbow Bridge, had pooled beneath it.

When the best laid plans for Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell were created, the Bureau of Reclamation “promised the Sierra Club, other conservationists, and the Navajo Nation that the waters of the lake would not encroach on the bridge—obvious flummery for anyone who could read a contour map.” The Bureau argued further that the water would not “erode or undermine the bridge—an argument impossible to validate, except as the smoke screen it obviously was” (Fowler).

To fight the Bureau of Reclamation, the Navajo People went to the Navajo Nation legal services division and asked them to help intervene. Ultimately, they assembled a panel of elders from the tribe who were tribal experts on ceremonial singing and chanting. Native Americans are known to be private about their ceremonies, stories, and religions, but for this occasion, it was decided that “The gods will not object when we, their people try to protect their own sacred places and bodies.” (Luckert 1977: vii –Fowler, 2011) The person assigned the task of helping to save Rainbow Bridge from the rising waters of the lake was Karl Luckert. He “published the Navajo Mountain and Rainbow Bridge Religion in 1977” (Fowler).

The only immediate relief from the Bureau of Rec. was to build boat docks down the canyon from the bridge—ultimately making it easier for tourist to access it. They did encourage people to not walk under the bridge, as it is offensive to the Navajo.

Since then, more changes have been made. In 2011, I volunteered for the National Park Service(NPS) at Glen Canyon. The NPS is extremely protective of Rainbow Bridge and the culture that surrounds it—not only Native Americans, but all Americans as well as foreign visitors. At the 2010 Centennial of Rainbow Bridge National Monument, the slogan for the celebration was “Spanning Cultures in a Sacred Landscape.”

There are current assurances that the waters of Lake Powell will never reach Rainbow Bridge again. I think the main one is logistical: If the lake gets to full on a big runoff year, they can’t release the water fast enough to avoid disaster. They experienced this very problem in 1983. A story that is told well in The Emerald Mile, by Kevin Fedarko. Since that time, lake levels stay reasonable, and people dock their boats and walk 1.25 miles to see Rainbow Bridge from the lakeside. If they have done their research, they will learn that they are visiting the Home of the Rainbow.

To avoid our trip around Navajo Mountain and the hike to Rainbow Bridge being anticlimactic, Ryan and I stayed on the east side of the Rainbow. Lee and Carolyn joined the throngs of people coming from the boat docks on the other side, but only to deposit our trash in the receptacles provided by the park service. They really took one for the team that day.

Ryan and I are visitors of Lake Powell and we enjoy it, but we didn’t want the commercialism of real life to taint this journey that we were on. We didn’t want to be touched by the people who could not possibly understand what we were doing—not that they would have asked. We were just more comfortable staying away.

We did see a few venturous souls who journeyed up the trail a little farther than most, and that was ok. At least they were trying to be different, to step outside the norm and experience more of what the area had to offer.

Most just tromp off the boat, walk up the hill, take a picture, and tromp back to the boat where radios blare from wakeboard towers and boat captains vie for the best docking space—most are mad at some other guy for taking his spot, not to mention mad at their wives for making them come see the dumb bridge anyway! “For the love of God, can’t we just go ski some more? And hey! Get me a beer!”

Yeah, no thanks. Definite kudos to Lee and Carolyn for dumping the trash.

It was bitter-sweet to leave the bridge and head back up the canyon, but we had a journey to finish. With Buddha’s blessing, we would trek on, but not before his photo op.

We camped that night at Oak Creek. Real, flowing water. I was exhausted and afflicted by knee pain that I had never had before, and have never had since. Serious, like I could barely put one foot in front of the other, knee pain. I went to Oak Creek and sat down in it, effectively icing my knee for as long as I could manage to stay in the surprisingly cold water. It was refreshing and luxurious.

Carolyn forgot her lip balm and was running low on food, regularly claiming “ I am going to die out here!” I gave her lip balm, and Ryan snuck food to her when Lee wasn’t watching—he was teaching her a lesson about packing better. We just thought she should eat.

Ryan always over-packs and carries more water than any self-respecting camel could hold while walking through the desert. We teased him relentlessly about the weight of his pack and somehow the subject of whether or not he really “needed” a signal mirror came up. As it turns out, Lee, who teased him more than the rest of us, needed that signal mirror.

Lee managed to get sand in his eye and the mirror came in handy while trying to extract it. He has never begrudged Ryan’s full pack again.

Leaving Oak Creek, the trail remained rock strewn and my knee remained sore. It’s a day that I survived, but I don’t remember. We passed Owl Bridge and we hiked through Surprise Valley. It is with regret that I only have pictures to remember this by.

At the end of this fourth day we all found solace on a ledge where we rested our wounded tired bodies and watched the sunset over a land that beckons to a thirsty soul. The country is rough, dry, harsh, and unforgiving. But at the same time is nourishing, fulfilling, and spiritual.

Even Lee, who believes in nothing and is a bit skeptical of everything, said so. When I asked him to describe our trip he said, “I don’t know. That was the best trip ever! I’ve never had an experience like that!”

When I asked him why, he said “it was magic.”

The next morning the spell was broken when we had to walk a bit further, to cell service, to let Eric know that we would be ready early. Several hours early. We left a message.

We walked on and eventually a worn out, old pickup came tearing down the road, passed us and turned around. We were a little worried—ok, more than a little. There are stories of hikers getting harassed by young Navajos with something to prove. We only had our permit to protect us.

The guy jumped out of the truck and walked toward us, but stopped and opened the tailgate, speaking only one word in the process: Eric.

We threw our packs in the bed and jumped in. This was our ride.

Coming full circle to the Hogan where we started, we were ready for showers, real food, real beds, and a drink. All of this hiking, exploring, communing with nature and the gods, makes you tired, hungry and thirsty.

Naturally though, as we emerged back into society, culture shock ensued. Bluff, UT was our refuge that night and it was bustling with river runners, hikers, and other tourists just like us; all searching for something different, something special, and something filled with the vibrancy of rainbows.

I appreciate your time, and I value your feedback. Please take a moment to rate or share this article below. Your comments are also welcome. All the best to you! Until next time ~ Jennifer

Citations: I relied on outside information and some personal oral history for this article. I attempted throughout to keep up with some of it without drawing attention from the story. Below is a list of the books and websites where I found much of my information. Additionally, the information in normal text is all me telling the story. The information that is formatted in Italics and below the sub-headings is meant to be informational to add context and other important ideas that add to the story. It is my hope that this is clear. There is no way that these few words can convey the scope of the subject matter. I sincerely hope that I have inspired some to search on and discover more of an enchanted place. Thank you.

http://navajopeople.org/navajo-hogans.htm

http://navajoland.org/build-a-hogan.html

The Glen Canyon Country—A Personal Memoir; Don Fowler, 2011

http://www.summitpost.org/navajo-mountain-ut/397784

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navajo_Mountain

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/laccolith

https://www.nps.gov/rabr/learn/historyculture/upload/RABR_adhi.pdf

http://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_solanaceae.php

https://www.desert-alchemy.com/flower-essence/sada/